Introducing programming to the curriculum

Programming is not only for computer hackers, it can also help teachers to engage their students in science subjects and inspire start ups to discover new cancer treatments.

Almost 60 teachers working in upper secondary schools in Oslo visited Oslo Cancer Cluster Innovation Park and Ullern Upper Secondary School one evening in the end of March. The topic for the event was programming and how to introduce programming to the science subjects in school.

“The government has decided that programming should be implemented in schools, but in that case the teachers first have to know how to program, how to teach programming and, not least, how to make use of programming in a relevant way in their own subjects.”

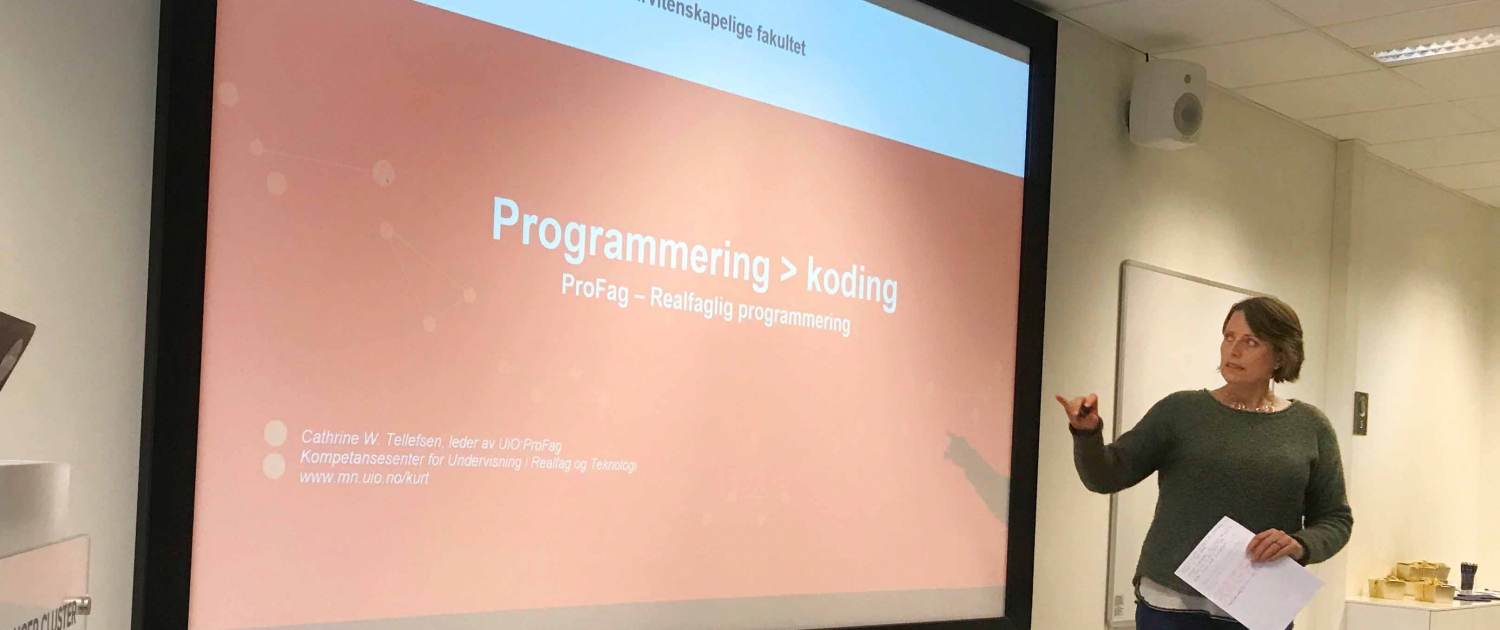

This was how Cathrine Wahlström Tellefsen opened her lecture. She is the Head of Profag at the University of Oslo, a competence centre for teaching science and technology subjects. For nearly one hour, she talked to the almost 60 teachers who teach Biology, Mathematics, Chemistry, Technology, Science Research Theory and Physics about how to use programming in their teaching.

Programming and coding

“Don’t forget that programming is much more than just coding. Computers are changing the rules of the game and we have gained a much larger mathematical toolbox, which gives us the opportunity to analyse large data sets,” Tellefsen explained.

Only a couple of years ago, she wasn’t very interested in programming herself, but after pressures from higher up in her organisation, she gave it a shot. She has since then experienced how programming can be used in her own subject.

“I have been a Physics teacher for many years in an upper secondary school in Akershus, so I know how it is,” she said to calm the audience a little. Her excitement over the opportunities programming provides seemed to rub off on some of the people in the room.

“In biology, for example, programming can be used to teach animal population growth. The students understand more of the logic behind the use of mathematical formulas and how an increase in the carrying capacity of a biological species can change the size of its population dramatically. My experience is that the students start playing around with the numbers really quickly and get a better understanding of the relationships,” said Tellefsen.

When it was time for a little break, many teachers were eager to try out the calculations and programming themselves.

Artificial intelligence in cancer treatments

Before the teachers tried programming, Marius Eidsaa from the start up OncoImmunity (a member of Oslo Cancer Cluster) gave a talk. He is a former physicist and uses algorithms, programming and artificial intelligence every day in his work.

“OncoImmunity has developed a method that can find new antigens that other companies can use to develop cancer vaccines,” said Eidsaa.

He quickly explained the principals of immunotherapy, a cancer treatment that activates the patient’s own immune system to recognise and kill cancer cells, which had previously remained hidden from the immune system. The neoantigens play a central role in this process.

“Our product is a computer software program called Immuneprofiler. We use patient data and artificial intelligence in order to get a ranking of the antigens that may be relevant for development of personalised cancer vaccines to the individual patient,” said Eidsaa.

Today, OncoImmunity has almost 20 employees of 10 different nationalities and have become CE-marked as the first company in the world in their field. (You can read more about OncoImmunity in this article that we published on 18 December 2018.)

The introductory talk by Eidsaa about using programming in his start up peaked the audience’s interest and the dedicated teachers eagerly asked many questions.

Programming in practice

After a short coffee break, the teachers were ready to try programming themselves. I tried programming in Biology, a session that was led by Monica, a teacher at Ullern Upper Secondary School. She is continuing her education in programming now and it turns out she has become very driven.

“Now you will program protein synthesis,” said Monica. We started brainstorming together about what we needed to find out, which parameters we could use in the formula to get the software Python to find proteins for us.

Since my knowledge in biology is a little rusty, it was a slow process. But when Monica showed us the correct solution, it was surprisingly logical and simple. The key is to stay focused and remember to have a cheat sheet right next to you in case you forget something.