Olweus wins prestigious award

Professor Johanna Olweus has been awarded the ERC Consolidator Grant for her cancer research project on immunotherapy.

The Norwegian cancer researcher Johanna Olweus was awarded a prestigious grant from the European Research Council (ERC) last week, as the only Norwegian scientist within Life Sciences. Olweus is Head of Department of Cancer Immunology at the Institute for Cancer Research and Professor at the University of Oslo.

Olweus will receive 2 million euros over a 5-year-period for her research project in immunotherapy called “Outsourcing cancer immunity to healthy donors”.

“Immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of metastatic cancer the last few years,” said Olweus. “Still, there is no curative treatment for many patients.”

Donor technology to save lives

Olweus worked in transplantation immunology when she first thought of the idea behind her innovative research. She saw that organ rejection triggers powerful immune responses, which could be used in cancer treatments too.

“The mechanism behind this rejection is connected to differences in the immune systems between the donor and the recipient,” said Olweus. “We have shown that we can utilise this mechanism to reject cancer cells in the laboratory.”

The treatment she has developed evades the patient’s tolerance to his or her cancer cells by utilising the immune response of a donor.

“We are exploiting the differences in the immune systems to mimic the rejection response you see in organ rejection and we target it to a specific cell type,” Olweus explained.

Her research group takes T cells from a healthy donor. Then, they use their patent-protected technology to select T cells with anti-tumour reactivity from the repertoire of the donor’s T cells. They next identify the T cell receptors (TCRs) from the selected T cells that can efficiently recognise specific peptides (fragments of proteins) expressed by the cancer cell. Upon reinfusion into the patient, such TCRs can work like heat-seeking missiles. They will make the T cells search for the cancer cells and destroy them.

(Read more about T cell immunogene therapy further down in this article)

What’s next?

Olweus has already demonstrated evidence in pre-clinical experiments on human cells from cancer patients in the laboratory and in mice that the treatment can work. Now, she is in advanced planning stages for clinical trials, in which the treatment will be tested on cancer patients.

“This award means I have long-term funding to perform the project and can secure talented personnel to do the science,” Olweus said.

Olweus is also in the process of exploring the commercialization potential of the T cell receptors that her research group has generated. The group has secured a prestigious commercialisation grant from Novo Holdings to possibly start a company.

“We have developed TCRs that can work in multiple haematological cancers. First, we need to show clinical efficacy. In the long term, we hope to cure some of the patients for whom there is currently no cure,” said Olweus. “To get the science implemented in clinical trials is really crucial.”

Olweus stresses the need for manufacturing facilities in Norway for cell- and gene therapies. To achieve this, she thinks there needs to be collaboration between regulatory authorities, clinicians and researchers.

“It is important that the Nordic medicinal agencies seize the opportunity to establish these therapies in the front line to make them available to patients in the Nordic countries,” said Olweus. “The Nordic countries could have a great advantage if the regulatory authorities are working together with the clinicians, academic scientists and also with industrial partners in early testing of new cell- and gene therapies.”

The Department of Cancer Immunology and the Department of Cellular Therapy have advanced plans for establishment of infrastructure for production of cells for gene therapy at Oslo University Hospital Radiumhospitalet in Oslo.

What is immunogene therapy based on T cells?

Olweus’ research is in a special area of cancer treatments called immunotherapy. This involves harnessing the patient’s immune system to create a response that will destroy cancer cells.

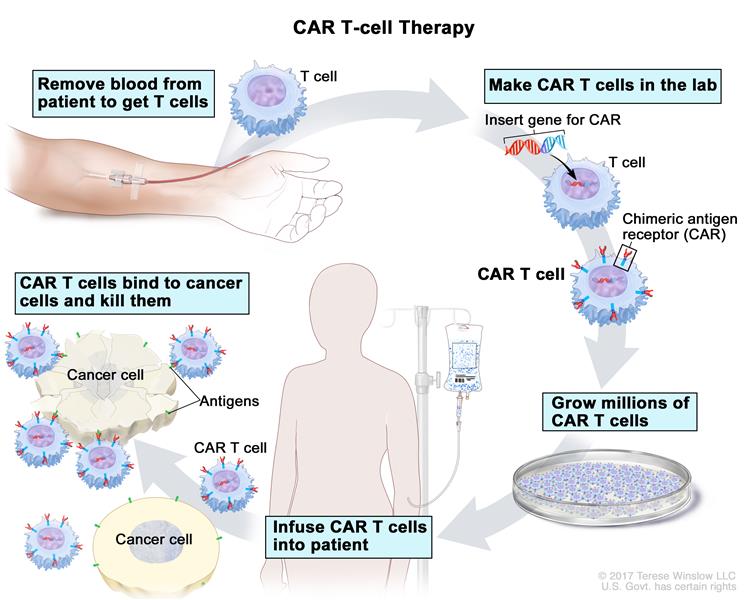

One category of immunotherapy is immunogene therapy. The first example of immunogene therapy that was approved by the FDA in 2017 involves the use of so-called CARs (chimeric antigen receptors), targeting CD19.

The process starts with the harvesting of the patient’s white blood cells from their blood, containing T cells. Then, the T cells are genetically modified in the lab to equip the cells with immune receptors that can target a molecule specific for B cells. Upon reinfusion into the patient’s blood, these T cells can then find the cancer cells and kill them, based on recognition of the B cell molecule called CD19.

This type of therapy has been immensely successful, curing up to 40-50% of patients that were previously incurable. The treatment has worked for patients with B cell cancers, such as B cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and B cell lymphoma.

The complete process of CAR T cell therapy to treat cancer. Illustration: National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov)

Not yet a cure for all patients

In spite of the great success of immunotherapies, such as checkpoint inhibition and CAR therapies, there is still no curative treatment option for the majority of patients with metastatic cancer (cancer that has spread). Checkpoint inhibition and various vaccination strategies rely on the patient’s own immune system, which often is insufficient in the end. In CAR therapies, the patient’s T cells are equipped with a reactivity that they did not have before, which can mediate cures. However, CAR 19 therapy does not cure 50-60% of patients with B cell cancers. Moreover, in spite of year-long efforts, no CAR therapy has yet been approved for other cancers than B cell cancers.

“The main reason is that there is a lack of good targets, which are highly expressed on the cancer cells and can be safely targeted,” said Olweus. “In the case of CARs targeting CD19, the normal and malignant B cells are killed alike, as CD19 is a normal, cell-type specific protein. This is, however, tolerated by the patient as we can live without normal B cells for prolonged periods. So you need to be sure that you can live without the normal counterpart of the cancer cell.”

CARs can only recognize targets in the cell membrane of the cancer cell. In contrast, a T cell receptor (TCR) is an alternative immune receptor that can recognise targets independently of where in the cell they are. Since more than 90% of proteins are inside the cell, gene therapy utilizing therapeutic TCRs can vastly increase the number of potential targets.

“The challenge for identification of therapeutic TCRs that target cell-type specific proteins is that the T cells in our own body have been trained to not recognise them,” said Olweus. “If not, we would all have autoimmunity. The technology we have developed can solve this challenge by utilization of donor T cells, that have not been trained not to recognize cells from another individual. This is where the mechanism of transplant rejection comes to use.”

There are two main challenges researchers are faced with when improving T cell therapy. The first is to identify new targets that are abundant in the cancer cells and can be safely targeted. The second is to identify immune receptors that recognize the targets with high efficacy and precision. Olweus’ research aims to answer both of these challenges.