Learning about the human brain

Oslo Cancer Cluster and Ullern Upper Secondary School arranged a work placement for students to learn about neuroscience at the University of Oslo.

Four biology students from Ullern Upper Secondary School spent two great days on work placement with some of the world’s best neuroscientists at the University of Oslo. In Marianne Fyhn’s research group, the students tried training rats and learned how research on rats can provide valuable knowledge about the human brain.

The Ullern students, Benedicte Berggrav, Lina Babusiaux, Maren Gjerstad Høgden and Emmy Hansteen, first had to dress in green laboratory clothes, hairnets and gloves. They also had to leave their phones and notepads behind, before enterring the animal laboratory where Marianne Fyhn and her colleagues work. Finally, they had to walk through an air lock that blew the last remnants of dust and pollution off them.

On the other side was the most sacred place for researchers: the newly refurbished animal laboratory. It is in the basement of Kristine Bonnevies Hus on the University of Oslo campus. We used to call it “Bio-bygget” (“the bio-building”) when I studied here during the ‘1990s.

Researcher Kristian Lensjø showed the four excited biology students into the most sacred place: the animal lab.

It is the second day of the students’ work placement with Marianne. The four biology students, who normally attend the second year of Ullern Upper Secondary School, have started to get used to their new, temporary jobs. They are standing in one of the laboratories and looking at master student Dejana Mitrovic as she is operating thin electrodes onto the brain of a sedated rat. PhD student Malin Benum Røe is standing behind Dejana, watching intently, giving guidance and a helping hand if needed.

“We do this so we can study the brain cells. We will also find out if we can guide the brain cells with weak electrical impulses. This is basic scientific research. In the long term, the knowledge can help to improve how a person with an amputated arm can control an artificial prosthetic arm,” Marianne explained.

“The knowledge can help to improve how a person with an amputated arm can control an artificial prosthetic arm.”

Dejana needs to be extremely precise when she connects the electrodes onto the rat’s brain. This is precision work and every micrometre makes a difference.

Training rats

The previous day, Maren, Benedicte, Lina and Emmy helped to train the rat on the operating table on a running course. Today, the Ullern students will train the other rats that haven’t had electrodes surgically connected to their brains yet.

“We will train the rats to walk in figures of eight, first in one direction and then the other”, the students explained to me.

We remain standing in the rat training room for a while, talk with Dejana and train some of the rats. Dejana tells me that the rats don’t have any names. After all, they are not pets, but they are cared for and looked after in all ways imaginable.

“It is very important that they are happy and don’t get stressed. Otherwise, they won’t perform the tasks we train them to do,” says Dejana. She and the other researchers know the animals well and know to look for any signs that may indicate that the rats aren’t feeling well.

“It is very important that they are happy and don’t get stressed.”

I ask the students how they feel about using rats for science.

“I think it is completely all right. The rats are doing well and can give us important information about the human brain. It is not okay when rats are used to test make-up and cosmetics, but it is a whole different matter when it concerns important medical research,” says Emmy and the other biology students from Ullern nod in agreement.

Understanding the brain

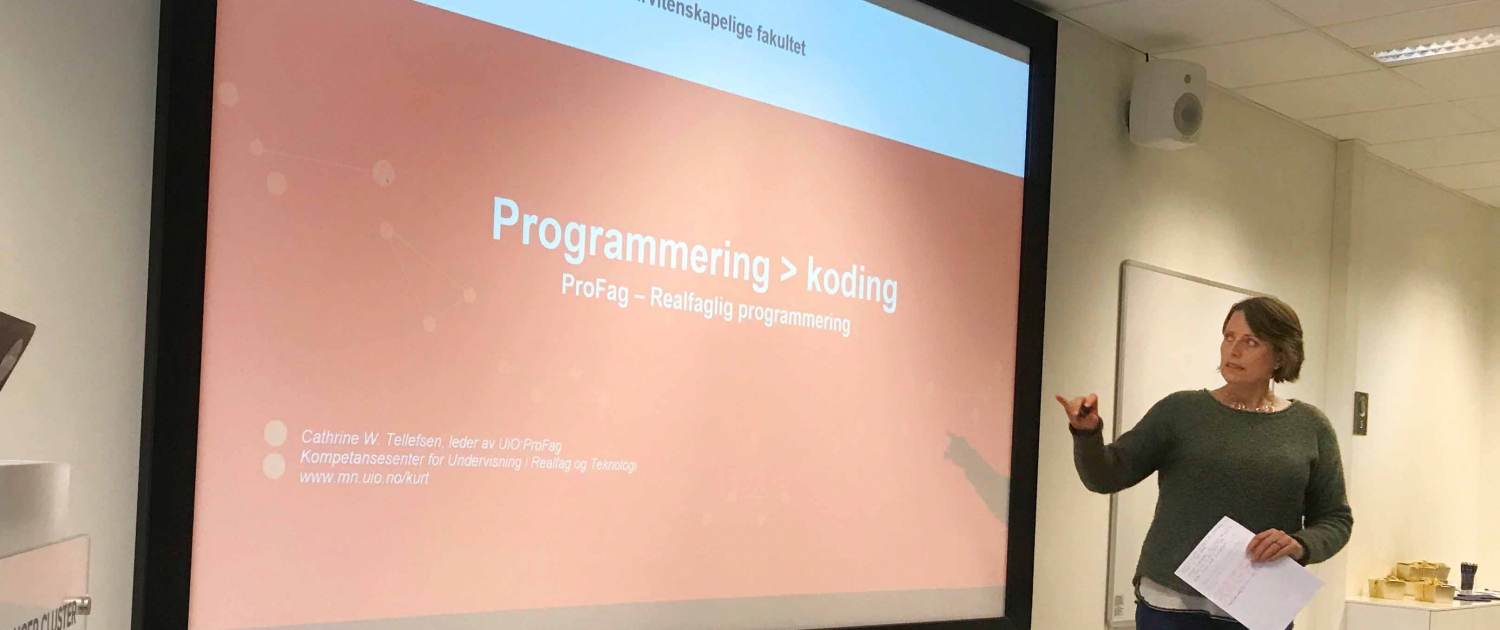

Marianne is the head of the CINPLA centre at the University of Oslo, where Maren, Benedicte, Lina and Emmy are on work placement for two days. Four other Ullern students, Henrik Andreas Elde, Nils William Ormestad Lie, Hans Christian Thagaard and Thale Gartland, are at the same time on a work placement with Mariannes research colleague, Professor of Physics Anders Malthe-Sørenssen. They are learning about methods in physics, mathematics and programming that help researchers to better understand the brain.

“CINPLA is an acronym for Centre for Integrative Neuroplasticity. We try to bring together experimental biology with calculative physics and mathematics to better understand information processing in the brain and the brain’s ability to change itself,” says Marianne.

Physics, mathematics and programming are therefore important parts of the researcher’s work when analysing what is happening in the rat’s brain.

If you think that research on rats’ brain cells sounds familiar, then you are probably right. Edvard and May-Britt Moser in Trondheim received the first Norwegian Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2014. The award was given to them for their discovery of a certain type of brain cells, so called grid cells. The grid cells alert the body to its location and how to find its way from point A to point B.

Marianne did her PhD with Edvard and May-Britt, playing an essential role in the work that led to the discovery of the grid cells. Marianne was therefore very involved in Norway securing its first Nobel Prize in Medicine.

The dark room

Another room in the animal section is completely dark. In the middle of the room, there is an enormous box with various equipment. In the centre of the box, there is a little mouse with an implant on its head.

In this test room, there is an advanced microscope. It uses a laser beam to read the brain activity of the mouse as it alternates between running and standing still on a treadmill.

The researcher Kristian Lensjø is back from a longer study break at the renowned Harvard University and will use some of the methods he has learned.

“I will train the mouse so that it understands that for example vertical lines on a screen mean reward and that horizontal lines give no reward. Then I will look at which brain cells are responsible for this type of learning,” says Kristian.

The students stand behind Kristian and watch the mouse and the computer screen. When the testing begins, they must close the microscope off with a curtain so that the mouse is alone in the dark box. Kristian assures us that the mouse is okay and that he can see what the mouse is doing through an infra-red camera.

“This room and the equipment is so new, we are still experiencing some issues with the tech,” says Marianne. But Christian fixes the problem and suddenly we see something on the computer screen that we have never seen before. It is a look into the mouse’s brain while it runs on the treadmill. This means that the researchers can watch the nerve cells as the mouse looks at vertical and horizontal lines, and detect where the brain activity occurs.

Research role models

The students from Ullern know they are lucky to see how cutting-edge neuroscience is done in real life. Marianne and her colleagues are far from nobodies in the research world. Bente Prestegård from Oslo Cancer Cluster and Monica Jenstad, the biology teacher at Ullern who coordinates the work placements, made sure to tell the students beforehand.

“This is a fantastic and unique opportunity for students to get a look into science on a high international level. They can see that the people behind the research are nice and just like any normal people. When seeing good role models, it is easier to picture a future in research for oneself,” says Monica.

“This is a fantastic and unique opportunity for students to get a look into science on a high international level.”

Monica and Marianne have known each other since they were master students together at the University of Tromsø almost twenty years ago.

“I know Marianne very well, both privately and professionally. She is passionate about her research and about dissemination and recruitment. She also works hard to create a positive environment for her research group. Therefore, it was natural to ask Marianne to receive the students and it wasn’t difficult to get her to agree,” says Monica.

Back in the first operating room, Dejana and Malin are still operating on the rats. They will spend the entire day doing this. It takes time when the equipment needs to be found and sterilised, the rats need to be sedated and then operated on as precisely as possibly. It is past noon and time for lunch for Marianne, Kristian and the Ullern students on work placement.

Before I leave them outside Niels Henrik Abels Hus at the Oslo University Campus, I take a picture to remember the extra-ordinary work placement. And not least: to store a picture of the memory in my own brain.

Finally, time for lunch! From the left: Emmy Hansteen, Benedicte Berggrav, researcher Marianne Fyhn, Lina Babusiaux, Maren Gjerstad Høgden and researcher Kristian Lensjø. Photo: Elisabeth Kirkeng Andersen.